Prior to last season, I wrote this article detailing the Wide Zone Offensive Scheme. SicEm365 has had a lot of new members join since then, and I think if you are going to understand one thing about Baylor football schematically, understanding the wide zone should be at the top of your list.

The piece has been updated to make it more succinct and more video examples have been added.

What Is Wide Zone, Anyway?

If you’ve paid any attention to Baylor football since offensive coordinator Jeff Grimes arrived in Spring 2021, you’ll know that Baylor’s offense is based on the wide zone. But as fans, we don’t want to only know the multiple-choice answer, we want to be able to explain a fill-in-the-blank. Baylor’s offense is built around the wide zone, you know that. But can you explain what that means? Hopefully, after this article, we’ll all be able to do just that.

The Offensive Line Creates A “Line of Force”

Baylor’s offensive line coach Eric Mateos has a very easy to understand 5-minute clip available on YouTube wherein he discusses how he wants his OL to “create a line of force” on every running play:

“The number one thing I want people to say when they watch our OL play is ‘Boy, they run off the football.’”

This is a key difference for how the offensive line blocks in wide zone. In other schemes — such as inside zone or duo— the emphasis for the OL is about bodying up the DL over you and generating vertical displacement. I.e., you’re matched up with a guy across from you, you’re engaging in a sumo match of sorts, and you want to push him farther back than he pushes you. Generally, these schemes revolve around double teams (two OL blocking a single defensive lineman) at the point of attack (where the ball is designed to go) which provides quick displacement.

In 2021, Baylor only ran wide zone. But this past year, they began to mix in some in some duo to take advantage of teams expecting the ball to go horizontally. Notice how in the below example the OL’s first steps are all vertical; they’re not running off the ball horizontally, they’re attacking vertically

The wide zone is very different. Most importantly: it is not about vertical displacement, it’s about horizontal displacement. While other run schemes want to push defenders as far back as possible, the wide zone wants to generate a horizontal line of force which naturally causes defenders to be in disadvantaged positions via movement as opposed to power.

If you watch a Baylor running play, you’ll notice that all of the OL move in unison “as one.” Mateos highlights this:

This is right after the snap. Notice how every OL “looks the same.” The play is going to their left, and they move as one. It’s really beautiful to see. And this does not happen by accident. This is the result of hours and hours of repetition during the off-season.

As a staff, they teach their OL that they can do one of three things on a play:

- “Reach” a defender (get to them on an even basis, essentially).

- “Stretch” a defender, which means moving with the defender horizontally without letting him into the primary gap.

- “Displace” a defender, which means to actively move the DL out of the hole. This is usually done in conjunction with a double team from the OL.

What the Running Back Reads

An iron rule of football is that players are never free-wheeling, even if it seems like they are. Wide receivers don’t get to run a route however they feel like; they count their steps and everything is honed to the finest detail. The same goes for running backs in the wide zone. They don’t just run to the playside and “feel it out.” They have required footwork and reads. “Instincts” in football really just mean how quickly you can process information in real-time, whether it’s conscious or not.

The basic rules for the running back in the wide zone are as follows:

- To start, the RB aims for the outside hip of the widest offensive blocker (either an offensive tackle or a tight end).

- This is different in “mid-zone,” which is the same play as wide zone except the RB aims for the outside hip of the offensive tackle even if there is an attached tight end (Baylor used this play with Abram in 2021 a ton). Below is an example of Dominic Richardson running mid zone in the Spring game. Mid zone is still an outside running play, it just makes it easier to cut the ball back up inside since your trajectory isn’t as wide.

- Notably, the RB forms his line of attack pre-snap; i.e., if he’s aiming for the outside hip of the tight end, it’s where the tight end is pre snap, he does not continually chase the tight end’s movement after the snap.

At Least 5 Steps

When the RB is attacking this line, he must take at least 5 steps before he can cut. This ensures that the defense “flows” towards the playside which makes a cutback more effective. If the RB cuts before pushing the ball playside for long enough, then defenses can anticipate the cutback and thwart it. If you scroll back up to watch the examples of Sqwirl and Dominic Richardson, you’ll notice they both take at least five steps before cutting the ball back.

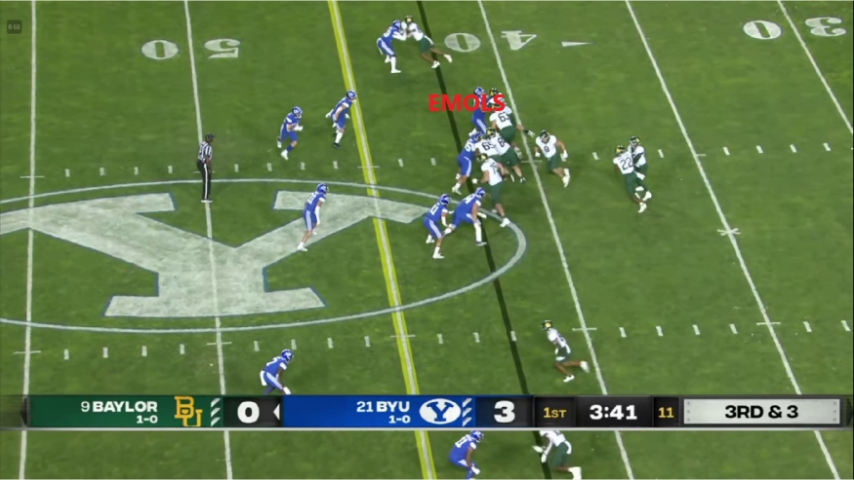

Read #1 – The End Man On the Line of Scrimmage (the “EMOLS”)

The RB’s primary read on every run is the “end man on the line of scrimmage (EMOLS).” This is exactly what it sounds like: he’s looking for the widest defender to the playside who is on the line of scrimmage. So he’s not looking at a linebacker who is several yards off the line; he’s usually looking at a defensive end or a linebacker who has walked up to the line of scrimmage.

This EMOLS is his primary read, and the read is very simple: is the EMOLS outside or inside the block? This first example below is what happens when the EMOLS gets hooked and is thus inside the blocker instead of outside. With the defender inside, the RB pushes the ball outside since there is now nobody setting the edge:

In the above play, Baylor has two tight ends lined up to the playside. The RB’s path is for the outside hip of the right tackle, which makes this mid zone. Once Abram sees the EMOLS get turned inside by the TEs, he bounces outside and turns upfield.

Helpfully, here is an example of what happens when the RB tries to push the ball outside even when the edge defender maintains outside leverage:

Most wide zone runs don’t bounce outside because defenses generally prefer for the EMOLS “set the edge” and force the RB back inside to more help defenders. So if that defender stays OUTSIDE, the RB moves to read #2 …

Read #2 – The Next Man in from the EMOLS

So, the RB’s primary read is that EMOLS. He sees whether that defender stays outside, tries to stunt inside, or gets hooked inside. If the EMOLS stays outside, the RB moves to read #2, which is simply the next defender on the line of scrimmage inside that EMOLS. So on a typical setup, the primary read would be a defensive end outside the playside offensive tackle, and the secondary read would be the defensive tackle who plays next to/inside that defensive end.

The read is the exact same as with the first read: if this secondary read stays outside, you cut inside. If he stunts inside, you go outside of him (which is between him and the EMOLS).

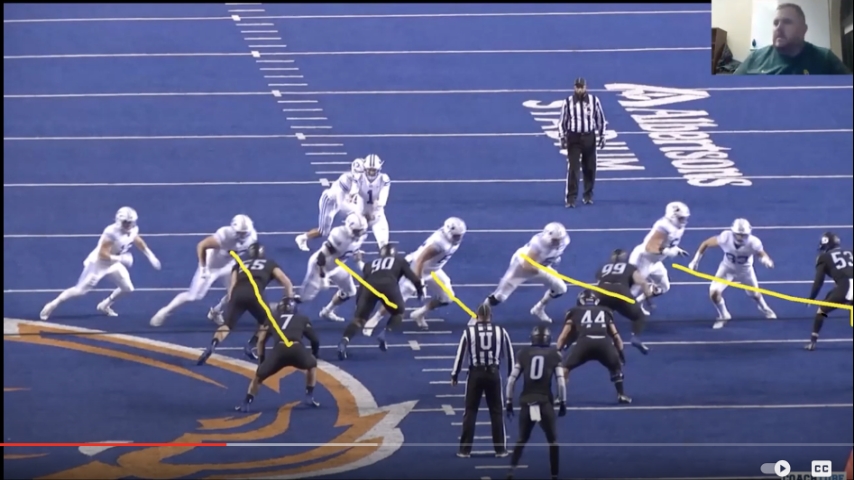

In the below example, notice the EMOLS, the RB’s primary read. The playside TE, #86 Ben Sims, blocks him but the defender stays outside, setting the edge. Thus, there is no point in the RB trying to get outside him, so he moves to his secondary read, who is the defensive tackle. The DT is being blocked by #58, Gavin Byers, the right tackle. Byers gets to the outside of the DT and turns him inside. This makes the read very clear: the defender is inside, so you go outside of him, between him and the EMOLS.

Put those first two examples together. Most simply, the RB is reading defenders to ensure he’s running into a gap where the defender ain’t. In the first example against BYU, the EMOLS gets pushed inside, so the RB goes where he ain’t, to the outside. In this second example against Texas, the EMOLS stays outside, so the RB moves to his secondary read, the DT. It’s the same idea here: go where the defender ain’t. The defender gets pushed inside, so he goes outside of him (which is in between the two defenders). If the defender stayed outside, the RB would have cut back inside of him. Speaking of which …

The Full Cutback

OK, so what happens if both the primary and secondary read defenders stay outside their blockers? This is when you see the full cutback. Here is a great example against BYU. The EMOLS is blocked by the tight end, #89 Drake Dabney, and the defender stays outside. The secondary read is blocked by the RT, #58 Gavin Byers, and the defender also stays outside. Thus, Abram sticks his foot in the ground and cuts up behind this secondary read and powers through the line of scrimmage.

At this point, the cutback can go as far back as makes sense for the RB. I think a lot of us remember this cutback …

This isn’t even a read as much as Baylor knew OU was overplaying this so hard. Grimes knew he was getting a 60+ yard run out of this before the snap. The line of scrimmage defenders slant hard toward the playside (staying outside), and the linebackers also overplay which leaves a gaping hole for the RB on the cutback.

Why The Wide Zone Works

I hope that this article gave a good, simple explanation of wid zone. The basics of this play are pretty fun. The OL moves as one unit of force, the RB executes some basic reads. The reads are basic, but still require a RB who can process information while he’s running with the ball. Other schemes are much more straightforward: the play is going to this gap, you go there. Baylor rarely calls plays with a predetermined read, so they need RBs with some intelligence and a good feel for the game (among other attributes).

It’s a really fun scheme because, as Eric Mateos says, even if the defense loads the box in theory the RB should be able to find a crease to get some positive yards. It’s very hard to make tackles in the backfield against this scheme.